Getting Started With TensorFlow¶

This guide gets you started programming in TensorFlow. Before using this guide, @{$install$install TensorFlow}. To get the most out of this guide, you should know the following:

- How to program in Python.

- At least a little bit about arrays.

- Ideally, something about machine learning. However, if you know little or nothing about machine learning, then this is still the first guide you should read.

TensorFlow provides multiple APIs. The lowest level API–TensorFlow Core– provides you with complete programming control. We recommend TensorFlow Core for machine learning researchers and others who require fine levels of control over their models. The higher level APIs are built on top of TensorFlow Core. These higher level APIs are typically easier to learn and use than TensorFlow Core. In addition, the higher level APIs make repetitive tasks easier and more consistent between different users. A high-level API like tf.estimator helps you manage data sets, estimators, training and inference.

This guide begins with a tutorial on TensorFlow Core. Later, we demonstrate how to implement the same model in tf.estimator. Knowing TensorFlow Core principles will give you a great mental model of how things are working internally when you use the more compact higher level API.

Tensors¶

The central unit of data in TensorFlow is the tensor. A tensor consists of a set of primitive values shaped into an array of any number of dimensions. A tensor’s rank is its number of dimensions. Here are some examples of tensors:

3 # a rank 0 tensor; a scalar with shape []

[1., 2., 3.] # a rank 1 tensor; a vector with shape [3]

[[1., 2., 3.], [4., 5., 6.]] # a rank 2 tensor; a matrix with shape [2, 3]

[[[1., 2., 3.]], [[7., 8., 9.]]] # a rank 3 tensor with shape [2, 1, 3]

TensorFlow Core tutorial¶

Importing TensorFlow¶

The canonical import statement for TensorFlow programs is as follows:

import tensorflow as tf

This gives Python access to all of TensorFlow’s classes, methods, and symbols. Most of the documentation assumes you have already done this.

The Computational Graph¶

You might think of TensorFlow Core programs as consisting of two discrete sections:

- Building the computational graph.

- Running the computational graph.

A computational graph is a series of TensorFlow operations arranged into a

graph of nodes.

Let’s build a simple computational graph. Each node takes zero

or more tensors as inputs and produces a tensor as an output. One type of node

is a constant. Like all TensorFlow constants, it takes no inputs, and it outputs

a value it stores internally. We can create two floating point Tensors node1

and node2 as follows:

node1 = tf.constant(3.0, dtype=tf.float32)

node2 = tf.constant(4.0) # also tf.float32 implicitly

print(node1, node2)

The final print statement produces

Tensor("Const:0", shape=(), dtype=float32) Tensor("Const_1:0", shape=(), dtype=float32)

Notice that printing the nodes does not output the values 3.0 and 4.0 as you

might expect. Instead, they are nodes that, when evaluated, would produce 3.0

and 4.0, respectively. To actually evaluate the nodes, we must run the

computational graph within a session. A session encapsulates the control and

state of the TensorFlow runtime.

The following code creates a Session object and then invokes its run method

to run enough of the computational graph to evaluate node1 and node2. By

running the computational graph in a session as follows:

sess = tf.Session()

print(sess.run([node1, node2]))

we see the expected values of 3.0 and 4.0:

[3.0, 4.0]

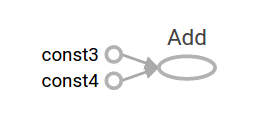

We can build more complicated computations by combining Tensor nodes with

operations (Operations are also nodes). For example, we can add our two

constant nodes and produce a new graph as follows:

from __future__ import print_function

node3 = tf.add(node1, node2)

print("node3:", node3)

print("sess.run(node3):", sess.run(node3))

The last two print statements produce

node3: Tensor("Add:0", shape=(), dtype=float32)

sess.run(node3): 7.0

TensorFlow provides a utility called TensorBoard that can display a picture of the computational graph. Here is a screenshot showing how TensorBoard visualizes the graph:

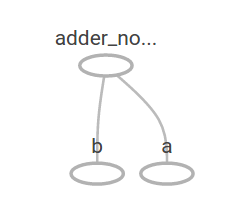

As it stands, this graph is not especially interesting because it always produces a constant result. A graph can be parameterized to accept external inputs, known as placeholders. A placeholder is a promise to provide a value later.

a = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

b = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

adder_node = a + b # + provides a shortcut for tf.add(a, b)

The preceding three lines are a bit like a function or a lambda in which we define two input parameters (a and b) and then an operation on them. We can evaluate this graph with multiple inputs by using the feed_dict argument to the run method to feed concrete values to the placeholders:

print(sess.run(adder_node, {a: 3, b: 4.5}))

print(sess.run(adder_node, {a: [1, 3], b: [2, 4]}))

resulting in the output

7.5

[ 3. 7.]

In TensorBoard, the graph looks like this:

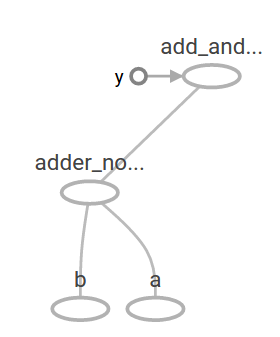

We can make the computational graph more complex by adding another operation. For example,

add_and_triple = adder_node * 3.

print(sess.run(add_and_triple, {a: 3, b: 4.5}))

produces the output

22.5

The preceding computational graph would look as follows in TensorBoard:

In machine learning we will typically want a model that can take arbitrary inputs, such as the one above. To make the model trainable, we need to be able to modify the graph to get new outputs with the same input. Variables allow us to add trainable parameters to a graph. They are constructed with a type and initial value:

W = tf.Variable([.3], dtype=tf.float32)

b = tf.Variable([-.3], dtype=tf.float32)

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

linear_model = W*x + b

Constants are initialized when you call tf.constant, and their value can never

change. By contrast, variables are not initialized when you call tf.Variable.

To initialize all the variables in a TensorFlow program, you must explicitly

call a special operation as follows:

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init)

It is important to realize init is a handle to the TensorFlow sub-graph that

initializes all the global variables. Until we call sess.run, the variables

are uninitialized.

Since x is a placeholder, we can evaluate linear_model for several values of

x simultaneously as follows:

print(sess.run(linear_model, {x: [1, 2, 3, 4]}))

to produce the output

[ 0. 0.30000001 0.60000002 0.90000004]

We’ve created a model, but we don’t know how good it is yet. To evaluate the

model on training data, we need a y placeholder to provide the desired values,

and we need to write a loss function.

A loss function measures how far apart the

current model is from the provided data. We’ll use a standard loss model for

linear regression, which sums the squares of the deltas between the current

model and the provided data. linear_model - y creates a vector where each

element is the corresponding example’s error delta. We call tf.square to

square that error. Then, we sum all the squared errors to create a single scalar

that abstracts the error of all examples using tf.reduce_sum:

y = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

squared_deltas = tf.square(linear_model - y)

loss = tf.reduce_sum(squared_deltas)

print(sess.run(loss, {x: [1, 2, 3, 4], y: [0, -1, -2, -3]}))

producing the loss value

23.66

We could improve this manually by reassigning the values of W and b to the

perfect values of -1 and 1. A variable is initialized to the value provided to

tf.Variable but can be changed using operations like tf.assign. For example,

W=-1 and b=1 are the optimal parameters for our model. We can change W and

b accordingly:

fixW = tf.assign(W, [-1.])

fixb = tf.assign(b, [1.])

sess.run([fixW, fixb])

print(sess.run(loss, {x: [1, 2, 3, 4], y: [0, -1, -2, -3]}))

The final print shows the loss now is zero.

0.0

We guessed the “perfect” values of W and b, but the whole point of machine

learning is to find the correct model parameters automatically. We will show

how to accomplish this in the next section.

tf.train API¶

A complete discussion of machine learning is out of the scope of this tutorial.

However, TensorFlow provides optimizers that slowly change each variable in

order to minimize the loss function. The simplest optimizer is gradient

descent. It modifies each variable according to the magnitude of the

derivative of loss with respect to that variable. In general, computing symbolic

derivatives manually is tedious and error-prone. Consequently, TensorFlow can

automatically produce derivatives given only a description of the model using

the function tf.gradients. For simplicity, optimizers typically do this

for you. For example,

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.01)

train = optimizer.minimize(loss)

sess.run(init) # reset values to incorrect defaults.

for i in range(1000):

sess.run(train, {x: [1, 2, 3, 4], y: [0, -1, -2, -3]})

print(sess.run([W, b]))

results in the final model parameters:

[array([-0.9999969], dtype=float32), array([ 0.99999082], dtype=float32)]

Now we have done actual machine learning! Although this simple linear regression model does not require much TensorFlow core code, more complicated models and methods to feed data into your models necessitate more code. Thus, TensorFlow provides higher level abstractions for common patterns, structures, and functionality. We will learn how to use some of these abstractions in the next section.

Complete program¶

The completed trainable linear regression model is shown here:

import tensorflow as tf

# Model parameters

W = tf.Variable([.3], dtype=tf.float32)

b = tf.Variable([-.3], dtype=tf.float32)

# Model input and output

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

linear_model = W*x + b

y = tf.placeholder(tf.float32)

# loss

loss = tf.reduce_sum(tf.square(linear_model - y)) # sum of the squares

# optimizer

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.01)

train = optimizer.minimize(loss)

# training data

x_train = [1, 2, 3, 4]

y_train = [0, -1, -2, -3]

# training loop

init = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess = tf.Session()

sess.run(init) # reset values to wrong

for i in range(1000):

sess.run(train, {x: x_train, y: y_train})

# evaluate training accuracy

curr_W, curr_b, curr_loss = sess.run([W, b, loss], {x: x_train, y: y_train})

print("W: %s b: %s loss: %s"%(curr_W, curr_b, curr_loss))

When run, it produces

W: [-0.9999969] b: [ 0.99999082] loss: 5.69997e-11

Notice that the loss is a very small number (very close to zero). If you run this program, your loss may not be exactly the same as the aforementioned loss because the model is initialized with pseudorandom values.

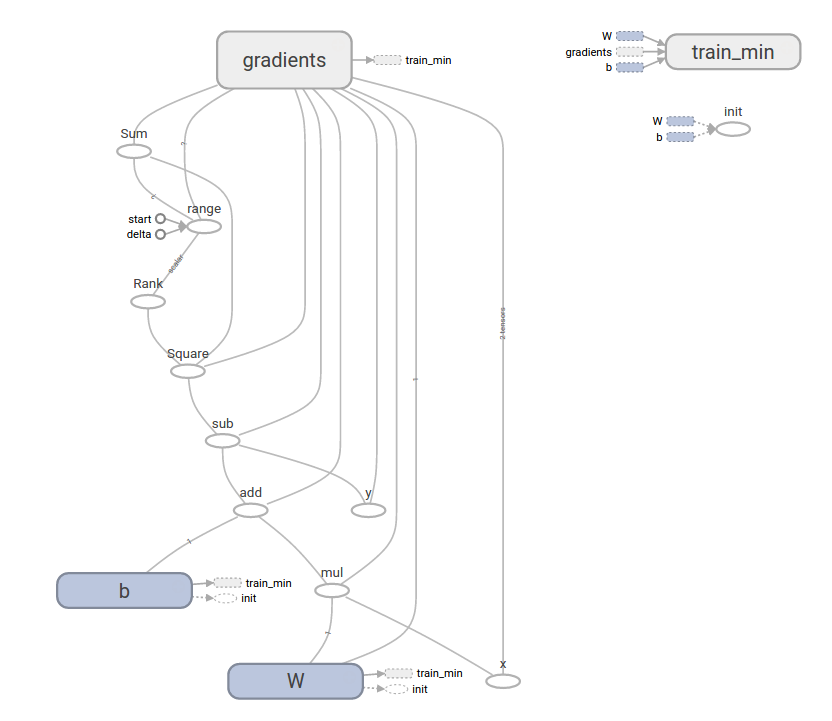

This more complicated program can still be visualized in TensorBoard

tf.estimator¶

tf.estimator is a high-level TensorFlow library that simplifies the

mechanics of machine learning, including the following:

- running training loops

- running evaluation loops

- managing data sets

tf.estimator defines many common models.

Basic usage¶

Notice how much simpler the linear regression program becomes with

tf.estimator:

# NumPy is often used to load, manipulate and preprocess data.

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

# Declare list of features. We only have one numeric feature. There are many

# other types of columns that are more complicated and useful.

feature_columns = [tf.feature_column.numeric_column("x", shape=[1])]

# An estimator is the front end to invoke training (fitting) and evaluation

# (inference). There are many predefined types like linear regression,

# linear classification, and many neural network classifiers and regressors.

# The following code provides an estimator that does linear regression.

estimator = tf.estimator.LinearRegressor(feature_columns=feature_columns)

# TensorFlow provides many helper methods to read and set up data sets.

# Here we use two data sets: one for training and one for evaluation

# We have to tell the function how many batches

# of data (num_epochs) we want and how big each batch should be.

x_train = np.array([1., 2., 3., 4.])

y_train = np.array([0., -1., -2., -3.])

x_eval = np.array([2., 5., 8., 1.])

y_eval = np.array([-1.01, -4.1, -7, 0.])

input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_train}, y_train, batch_size=4, num_epochs=None, shuffle=True)

train_input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_train}, y_train, batch_size=4, num_epochs=1000, shuffle=False)

eval_input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_eval}, y_eval, batch_size=4, num_epochs=1000, shuffle=False)

# We can invoke 1000 training steps by invoking the method and passing the

# training data set.

estimator.train(input_fn=input_fn, steps=1000)

# Here we evaluate how well our model did.

train_metrics = estimator.evaluate(input_fn=train_input_fn)

eval_metrics = estimator.evaluate(input_fn=eval_input_fn)

print("train metrics: %r"% train_metrics)

print("eval metrics: %r"% eval_metrics)

When run, it produces something like

train metrics: {'average_loss': 1.4833182e-08, 'global_step': 1000, 'loss': 5.9332727e-08}

eval metrics: {'average_loss': 0.0025353201, 'global_step': 1000, 'loss': 0.01014128}

Notice how our eval data has a higher loss, but it is still close to zero. That means we are learning properly.

A custom model¶

tf.estimator does not lock you into its predefined models. Suppose we

wanted to create a custom model that is not built into TensorFlow. We can still

retain the high level abstraction of data set, feeding, training, etc. of

tf.estimator. For illustration, we will show how to implement our own

equivalent model to LinearRegressor using our knowledge of the lower level

TensorFlow API.

To define a custom model that works with tf.estimator, we need to use

tf.estimator.Estimator. tf.estimator.LinearRegressor is actually

a sub-class of tf.estimator.Estimator. Instead of sub-classing

Estimator, we simply provide Estimator a function model_fn that tells

tf.estimator how it can evaluate predictions, training steps, and

loss. The code is as follows:

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

# Declare list of features, we only have one real-valued feature

def model_fn(features, labels, mode):

# Build a linear model and predict values

W = tf.get_variable("W", [1], dtype=tf.float64)

b = tf.get_variable("b", [1], dtype=tf.float64)

y = W*features['x'] + b

# Loss sub-graph

loss = tf.reduce_sum(tf.square(y - labels))

# Training sub-graph

global_step = tf.train.get_global_step()

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(0.01)

train = tf.group(optimizer.minimize(loss),

tf.assign_add(global_step, 1))

# EstimatorSpec connects subgraphs we built to the

# appropriate functionality.

return tf.estimator.EstimatorSpec(

mode=mode,

predictions=y,

loss=loss,

train_op=train)

estimator = tf.estimator.Estimator(model_fn=model_fn)

# define our data sets

x_train = np.array([1., 2., 3., 4.])

y_train = np.array([0., -1., -2., -3.])

x_eval = np.array([2., 5., 8., 1.])

y_eval = np.array([-1.01, -4.1, -7., 0.])

input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_train}, y_train, batch_size=4, num_epochs=None, shuffle=True)

train_input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_train}, y_train, batch_size=4, num_epochs=1000, shuffle=False)

eval_input_fn = tf.estimator.inputs.numpy_input_fn(

{"x": x_eval}, y_eval, batch_size=4, num_epochs=1000, shuffle=False)

# train

estimator.train(input_fn=input_fn, steps=1000)

# Here we evaluate how well our model did.

train_metrics = estimator.evaluate(input_fn=train_input_fn)

eval_metrics = estimator.evaluate(input_fn=eval_input_fn)

print("train metrics: %r"% train_metrics)

print("eval metrics: %r"% eval_metrics)

When run, it produces

train metrics: {'loss': 1.227995e-11, 'global_step': 1000}

eval metrics: {'loss': 0.01010036, 'global_step': 1000}

Notice how the contents of the custom model_fn() function are very similar

to our manual model training loop from the lower level API.

Next steps¶

Now you have a working knowledge of the basics of TensorFlow. We have several more tutorials that you can look at to learn more. If you are a beginner in machine learning see @{$beginners$MNIST for beginners}, otherwise see @{$pros$Deep MNIST for experts}.